I have been representing the criminally accused for nearly fifteen years—the entirety of my legal career. The first four years of my career were as a public defender—representing indigent Chicagoans on appeals of their criminal convictions. This included both direct appeals immediately after their convictions as well as appeals of dismissals of post-conviction or collateral petitions long after the original conviction was in place. I combed through records looking for evidence of trial error, constitutional violations, or other ways I might be able to help my clients get some sort of legal relief. What I didn’t do, however, was look for evidence of my client’s factual innocence. During my training and my time in the office, we never really spoke about wrongful convictions. It is embarrassing to even admit this, but I certainly didn’t think about my client’s potential innocence. I never even really stopped to think about how many innocent people might be convicted.

I started to consider the reality of wrongful convictions when I began working at Northwestern University School of Law in 2008. We were developing a clinic that was researching and exploring the prevalence of wrongful convictions amongst accused juveniles. We spent our time exploring the way police question and interrogate youth. We concluded that, in practice, police officers are trained to use techniques when questioning individuals that ran a significant risk of eliciting false information, leading to wrongful convictions. This remains, in my mind, no doubt true. But my inquiries were focused on mistakes and poor training, and the problem we sought to rectify assumed good faith on the part of the participants in the criminal justice system. I certainly was aware of wrongful convictions and the innocent being convicted, but I continued to view it as aberrant. Regardless of frequency, however, it was a problem that could be solved or at least addressed with proper training.

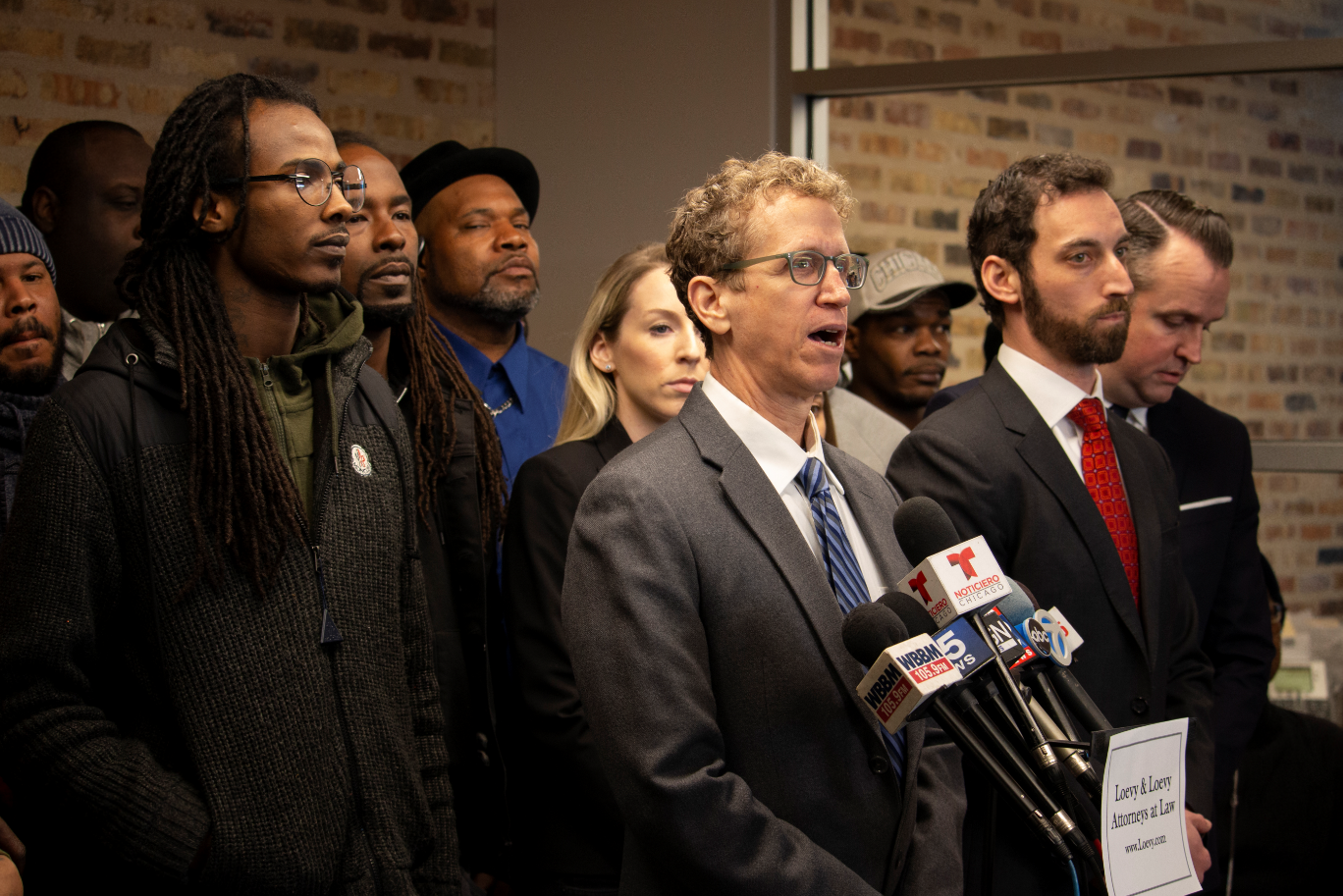

Over the last four years working with the Exoneration Project and Loevy & Loevy, my thought process has continued to evolve. Over and over again, through my work here, we see repeat players in the criminal justice system causing wrongful convictions on monumental scales. Whether it be bad officers like Sergeant Ronald Watts and his corrupt crew or Reynaldo Guevara and his team of detectives—or lying drug lab chemists fabricating results—or fake, criminal profiler “experts” who serve as pseudo truth detectors: the damage wrought by these individuals is extraordinary. I concluded that the fundamental, most overwhelming cause of wrongful convictions is intentional misconduct by bad actors. This is the root issue—but again, it is an issue that the system can solve by getting rid of the bad actors.

Recently, however, I’ve started again to think about wrongful convictions differently. Sure, the bad actors deserve their share of the blame for a system that has convicted, at bare minimum, 2,471 innocent people since 1989. But the blame really lies at the feet of a criminal justice system that allows these bad actors to flourish. All professions have bad actors—people who lie, cheat, or steal. You would think, however, that a system like criminal justice—where people’s very right to live in freedom is at stake—would be motivated to root out those bad actors. You would think that, but you’d be wrong.

It is not me, or other lawyers, who discovered that Ronald Watts or Reynaldo Guevara or whomever else was corrupt or a liar. The innocent individuals, their family members, and the community who were mistreated, framed, and the victims of rampant abuse of power knew. And they didn’t remain silent—far from it. They told everyone they could; everyone within the system who was supposed to stop it. They filed official complaints and they testified at trials. And they did it in astounding numbers.

Take the Sgt. Watts scandal. Watts led a group of officers who, for a decade, framed residents of the housing projects for drug and gun crimes. As of this date, 82 times courts have concluded that drug or gun convictions were made up. This group of officers spent a decade planting evidence, falsifying police reports, and lying under oath in what one court has called “one of the most staggering cases of police corruption in the history of Chicago.”

But it was no secret. Over and over again these individuals testified in court about this corruption—and astoundingly, we have identified roughly 655 times individuals filed formal complaints to the City against these officers.

655 times!

Everyone knew.

No one stopped it. No one cared.

That’s the root of the problem. The policies and practice of municipalities that allowed these bad actors to continue their misdeeds—to continue to punish the innocent and cheat the system—that is where the blame lies.

All professions have bad actors. Until we have a criminal justice system that cares about identifying and removing the bad actors, wrongful convictions will continue to flourish.