With this week’s amendment to the Patriot Act limiting the federal government’s surveillance of American phone records, people may believe that their private phone calls are actually more private. While the limits of the new legislation in actually protecting our privacy are a whole other topic, one thing is plain: it does not change the cell phone surveillance we are all potentially subjected to by local police officers using advanced technology to track our phones. The Chicago Police Department and many other state and local law enforcement agencies around the country are currently using cell phone surveillance technology that appears to allow them to track locations, build databases of political protesters, and even intercept the contents of phone users’ communications. The officers are often using this technology without a warrant, and may be secretly retrieving information from cell phone users who are just bystanders, not suspects in a case.

There is a growing public backlash about the program (including questions being raised by the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee and others), but because of its secrecy, there are still huge gaps in what we know about the program and the technology’s capabilities. Given the history of illegal spying on protesters for decades by the Chicago Police Department (the infamous “Red Squad”), people in Chicago should be particularly concerned.

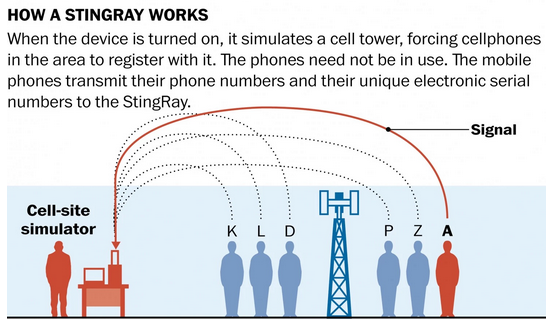

That’s where Freddy Martinez comes in. With his attorney Matt Topic of Loevy & Loevy, Mr. Martinez has been waging a legal battle against the Chicago Police Department and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office seeking information about the police’s use of the super-secret, military grade, cell phone tracking devices called “StingRays.” StingRays, also known as IMSI catchers, work by imitating a cell tower and essentially tricking the cell phones of everyone in a given area into sending data to the device instead of to a cell phone tower. It is not clear exactly what information the devices are capable of capturing, but they appear to be capable of eavesdropping on (or interfering with) phone conversations and text messages. The devices do not differentiate among people – they provide access to information from the cell phones of everyone in a given area, not just the phones of suspects under surveillance. Thus, this technology can affect everyone who carries a cell phone.

Although the devices can seriously infringe on the privacy of anyone using a cell phone, police departments are extremely secretive about when, where, and how they are using their spying capabilities. It is unclear how many local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies are using Stingray technology and how each agency is using the capability. So far, the ACLU has identified 52 agencies in 21 states and the District of Columbia that own StingRays. It is also unclear just how powerful the technology is – the manufacturer keeps all of the details about how it works as a closely guarded secret, and when the issue has come up, police departments have even dismissed criminal cases rather than divulge details about the technology.

In an earlier post, we wrote of Martinez’s initial suit under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) to learn about the Chicago Police Department’s use of the secret cell phone spying equipment. Numerous FOIA requests and two law suits later, the information is finally starting to trickle in. From the information that has come to light so far, it appears that the Chicago Police Department has spent at least half a million dollars on its StingRay program, is often deploying it without a warrant, and has minimal safeguard to protect against unauthorized use by officers. Stay tuned: this July, Martinez will be filing his brief to the court arguing for disclosure of the records.

Source: USA Today